Category Archives: Evangelical Christian fiction

Christian Writers and Christian Ignorance

One of the challenges for Christian writers (Catholic, Evangelical, Lutheran, all kinds) is that today’s Christians can be very ignorant of their own faith. And they are not doing anything to change that.

One of the challenges for Christian writers (Catholic, Evangelical, Lutheran, all kinds) is that today’s Christians can be very ignorant of their own faith. And they are not doing anything to change that.

My mom (born in 1927) went to an Evangelical and Reformed church in Brillion, Wisconsin. When she got to a certain age, she had to take a catechism class. They had to memorize the (Reformed/Calvinist) catechism in order to learn the basics of Christianity, before they were allowed to be confirmed and to join the church.

Other Christian children went to Catholic or Lutheran schools instead of the public schools, where they had religious instruction every single day.

Contrast that to today in which many people become Christians after watching an evangelist on television. They ask Jesus into their heart, but they don’t know what to do next. They may try going to a church, but if they haven’t been to a church before it may just seem too weird. Or they may pick a church based on the type of church music used, or prefer one where the sermons sound like they were taken from a New Age self-help book.

Christian writers, people like that are a part of your audience. And it’s your mission, whether you like it or not, whether you feel qualified or not, to plant ‘seeds’ of Christian knowledge in your readers. (It’s the Holy Spirit’s job to make those seeds grow.)

One seed you could plant is the idea that it’s the norm for a Christian to have a daily Bible reading time. At least, it’s the norm today. In the early Church, Christians got their ‘dose’ of Bible at the church service when Bible passages were read. That’s why even today we have the custom of having set Bible readings each Sunday (and at daily Mass for Catholics) and many churches have united in using the same Bible readings— so that my mother at a Presbyterian church and I at a Catholic church would hear the same Bible readings.

Of course, it’s easier to plant this particular seed if you write contemporary fiction. In fantasy, things are different. Imagine if C. S. Lewis had wanted to plant a seed about Bible reading in the Narnia books. In Narnia, Christianity is represented largely by the Person of Aslan, the Jesus-like Lion. There is no holy book or holy scroll mentioned in the story. I suppose Lewis could have mentioned his characters regularly talking to one another about their memories of encounters with Aslan. Well, we’re writers. I suppose we are creative enough to find ways to plant this seed in any type of fiction.

There are three major methods that people use for their daily Bible readings. One, popular among Catholics, Anglicans and Lutherans, is to read the assigned daily Mass readings for the day every day. Since these readings are read in daily Mass all over the world, people who do this are a part of the biggest Bible reading group in the world.

Another way is to follow a Bible reading plan which helps you to read through the whole Bible in a year. This is popular with Protestants— I know I had a guide to doing this printed in the back of a Bible I used during my Presbyterian childhood. There is also a Catholic guide to reading the Bible and Catechism in a year, put out by The Coming Home Network International. This is also good for Protestants who want to read the Deuterocanonical books also. (Both the King James Version translators and Martin Luther translated these books. These ‘Apocryphal’ books were not removed from English Bibles until much later. German Protestant Bibles still have them, tucked away between the Testaments.)

The third way of managing daily Bible reading is just picking and choosing passages. Some Christians are led astray by this: they may read the same few books over and over because they are familiar, or they may get into obscure Bible passages which they misunderstand. (This problem is why I encourage folks to read Bible commentaries by qualified Bible scholars, and why we attend churches with trained pastors who can help us through the difficult bits.)

Writers who are Christians may write ‘Christian fiction’ or may write for the mainstream market. But in either case, when you get known as a Christian writer, people will look up to you as a Christian leader. So we need to do our own Bible reading so we can pass on what we’ve learned through our fiction— or at least not lead people astray. (I must now end this post since I haven’t done my daily Bible reading yet today. I’m doing Genesis and Psalms with a commentary, as well as reading the Catechism passages from the Coming Home Network guide. You don’t want to know how many years it’s taking me to ‘read the Bible and Catechism in a year!)

Nominal Christians in Fiction and Real Life

Particularly for authors who are Christians of one sort or another, or authors who write for the Christian fiction markets, it is important to distinguish between Christians and nominal Christians.

Particularly for authors who are Christians of one sort or another, or authors who write for the Christian fiction markets, it is important to distinguish between Christians and nominal Christians.

In the United States, a person can follow any religion he likes, or no religion. And he can call himself a Christian whether or not that is particularly true. So there are a lot of people walking around with the ‘Christian’ tag on them who do not meet the normative definition of ‘Christian.’

Some Christians say that real Christians are ones that have had a ‘born again’ experience that they remember, or that have gone forward at a ‘altar call’ in Evangelical churches that have that practice. Other Christians say that being an active Christian can start at the sacrament of baptism, even an infant baptism, and can continue as a child is raised in a Christian home where prayer and church attendance are the norm.

A nominal Christian is a Christian ‘in name only.’ Why does he take the name of Christian? For some people, claiming Christianity as a religion is just another way of saying ‘my family is not Jewish.’ If they have parents, grandparents or great-grandparents who were raised as Christians, they feel they are Christian enough— they are just not ‘fanatics’ about it.

Other people honestly think that if they believe in God and sometimes ask this God for stuff, like help in an emergency or a winning lottery ticket, that makes them Christian, unless their family was Jewish or they have taken up Buddhist meditation.

It does not help that in addition to the faithful Christians— Protestant and Catholic— who believe something that a Christian from 200 years ago would recognize as Christian, there are also very progressive Christians who make headlines. For example, some progressive Christians have blessed abortion centers and said that committing abortions is what Jesus would do. That reinforces a perception that in Christianity, anything goes and you can believe any old thing and it can be part of Christianity.

Nominal Christianity is not the same thing as progressive Christianity. Progressive Christians, as far off from the New Testament as their faith can be, are living a faith that they believe is the modern version of Christianity. Nominal Christians aren’t actively practicing any faith at all. They don’t usually know enough about Christianity to know there is something missing in their faith life.

In fiction, nominal Christians play a role in Christian fiction often by being an obstacle or a challenge to active Christians. In the ‘Left Behind’ series, the main characters included nominal Christians who became real Christians after the shock of the ‘rapture’ event.

In secular fiction, nominal Christians are often seen as sensible and non-fanatic Christians by those writers who know little. Though I’ve never read a book in which a man who doesn’t own a Koran, has never fasted for Ramadan, and who has never been to a mosque or said even one of the five daily Muslim prayers is named as a ‘non-fanatic Muslim.’ Muslims are expected to have some hints of their faith in their lives, both in fiction and in real life. Christians should have that as well. If they don’t, but still say they are Christians, we may suspect that perhaps they are nominal Christians.

Authors who know better should never present nominal Christians as ‘better’ Christians, any more than the no-mosque, no-prayer guy is a ‘better’ Muslim. Religions, both in the real world and our fictional worlds, have content. Nominal Christians, or nominal Muslims, or nominal Buddhists lack that content and so should not be representative of those faiths.

The Great Deception in Christian Fiction

Some people know everything there is about Christian fiction. Sometimes without actually reading a single work of Christian fiction. But they won’t tell you the important thing.

Some people know everything there is about Christian fiction. Sometimes without actually reading a single work of Christian fiction. But they won’t tell you the important thing.

One of my pet peeves is that the term ‘Christian fiction’ is used as if it just naturally excludes Catholic authors— even if the person using the term doesn’t deny that Catholics are Christians.

Which leads me to a hint about the Great Deception: commercial Christian fiction is meant to make readers think that ‘Christian’ means ‘Christians-like-us.’

I once read a book telling how to write for the (evangelical) Christian fiction market. It said that if the church in your book is Grace Baptist Church or Faith Methodist Church, rename it. Make it Grace Church or Faith Community Church. Which made me gleefully think: if I change Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church to just Our Lady of Lourdes Church, no one will suspect we’re Catholic!

There is an incredible amount of diversity among different churches in the Evangelical category. Some baptise infants, others have believer’s baptism which excludes infants. Some teach that ‘once saved, always safe,’ while others teach that you can lose your ‘saved’ status by rejecting Christ and Christianity. Some Evangelicals— those in Lutheran churches— have liturgical worship. Other evangelicals do not. Some Evangelicals believe that the Rapture theory is a Bible-based End Times theory, others do not.

If the (Evangelical) Christian fiction author has to make every (Evangelical) reader feel that the book is about ‘Christians-like-us,’ there are a lot of things that can’t be mentioned. Baptisms, the events of a church service, how Holy Communion is done…. If one is not careful, all that is left of the faith is just a bunch of common Evangelical faith platitudes, in a bland story that tries to offend no one.

The famous best-selling Left Behind series ignored the rules. It was centered around a controversial belief about End Time events— the Rapture theory. I went to many kinds of Evangelical/Protestant churches in my earlier life, but I never went to one that taught the Rapture theory. There are loads of ‘Bible-believing’ Christians who don’t accept the Rapture theory. One might think that the authors of Left Behind would have been cautioned to be less controversial. But they went forward with their series based on End Time events that many Christians don’t believe in— and people read it. Even people who didn’t agree with the End Time theory, but liked the books because of their exciting story.

Now, I know some Christian fiction readers are wedded to the ‘Christians-like-us’ deception. They would not accept as Christian fiction a book with a Lutheran church instead of a ‘Community’ church, or one that differed from their own church’s practice on baptism, or a book that said taboo words like ‘darn’ or ‘heck’ or in which characters played cards or danced.

But most Christians are more grown-up. They know that the Christian world is full of people who do things differently. Since most Christians read more secular fiction than Christian fiction, they are more open towards ‘naughty’ things like characters who dance or drink a beer, but insist on more exciting plots than some Christian publishers accept.

When a Christian author is NOT seeking publication by one of the Christian traditional-publishers, the question becomes, should you tag your book ‘Christian fiction’ if it doesn’t try to be ‘generic Christian?’ Will that offend more potential readers than it attracts?

I don’t know that there is an easy answer to that. SOME readers need the comfort of Christian fiction that is just like the Christian publishers produce. Others are suspicious that ‘Christian fiction’ means fiction that is more bland than the secular fiction they prefer. But on the other hand they may be tired of the anti-Christian stuff allowed in secular fiction now, and long for a Christian fiction that is more to their taste.

The ultimate answer for the Indie writer of Christian faith is to experiment with the Christian tag and with the level of Christian content until you find out what works with your particular fiction and your reader-base.

Bad Novel Ideas for New/Young Christian Authors

Can you spot the kitten sleeping in this boot?

When you are young and/or new to writing, you may go through a phase where you are not sure what kind of writing ideas to have. Some of the early ideas are sure to be bad ones.

If you are also some sort of Christian, you may feel you need to write ‘Christian fiction,’ whether you have ever read ‘Christian fiction’ or not. One problem with that is that most of us think of Evangelical Christian fiction when we hear the words ‘Christian fiction.’ If you are Catholic or LDS or even a non-evangelical Protestant, Evangelical-style fiction likely won’t be right for you.

The common bad writing ideas will trip writers up no matter their denomination. They are ideas lots of Christian writers have that few Christian readers will buy. Since many naive Christian writers self-publish these novels anyway, you will have much competition for a tiny share of readers.

Retold Bible Stories – Have you ever met someone who was just dying to read the story of King David from his favorite goat’s perspective? Or the life history of Hosea’s wife? Maybe if you are a noted Biblical scholar whose Bible commentaries are traditionally published and well-known, you could do this without boring or offending all potential readers. For the rest of us, we need a better idea.

Allegories – The famous book ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ is a Protestant allegory about the Christian life. I read it when I was a Protestant, and liked it. But that didn’t mean I was raiding the bookstores for more allegories to read! The Narnia series contains allegory, but also has a lot of content that isn’t direct allegory. But even this less-allegorical type isn’t an easy sell to Christian publishers or readers. If your planned story has a Jesus-character in it, like Aslan, perhaps you should think again.

Conflict-free Historicals – Prairie romance and Amish romance are popular escapist forms of Christian fiction. Many Christian readers want to escape from their current woes where they get mocked at work for being a Christian. But Amish and prairie stories have to be realistic enough to show real conflicts. Conflict is the life blood of fiction. Even escapist fiction.

The best thing the would-be Christian novelist can do is read within the genre. Find out what books are selling well, and read them. If you are not Evangelical, look for authors from your own faith background and read their books. If you can’t find any sort of Christian fiction that you like and that inspires you with writing ideas, maybe you should consider secular fiction. There ARE Christians who write for the secular market, like Dean Koontz. That might be what you are called to do.

How to show Christian worldview in fiction, part 1

When asked what they like about Christian fiction, people often say ‘it has a Christian worldview.’ They don’t say ‘when I read the book it felt like getting a really nice sermon.’ But how exactly do you go about showing a Christian worldview? This series of posts will help show you. [Note: ‘Christian’ here includes all followers of Christ, including Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Lutherans, Anglicans, Moravians, and LDS.]

One essential is this: Christian fiction takes place in a certain type of world. In this world, God is real, discoverable, and loves you. What does that mean?

God is real. Not maybe real or might-be real, or real-for-me-not-for-you, but real, like a nuclear explosion and the science behind it. The secular world likes to divide the world like this: there are the hard-nosed, logical, scientific-method thinkers who are all secularists-like-me, and the airy-fairy ‘spirituality’ sort who make a ‘leap of faith’ into the land without logic. Don’t you believe it. For the hard-nosed logical, scientific-method Christian, becoming a Christian isn’t based on ‘blind faith’ but on a logical examination of the evidence.

God is discoverable. There are two ways God is discoverable by man. One, God has revealed Himself in certain events— such as the deliverance of the people of Israel from slavery in Egypt. The events of that delivery— the ten plagues, the parting of the Red Sea— are commemorated among the descendants of the Israelites, modern-day Jews, to this day. And there is the event of the resurrection of Jesus Christ. There have been people who sought to debunk Christianity by examining the events of the crucifixion and resurrection as recorded in the Gospels, who have instead come to the conclusion that Christianity is true. There are also the words of prophets raised up by God, who in many cases have predicted events that have come to pass.

Another way that God is discoverable is through nature. St. Paul writes that even the Pagans have knowledge of God. “Because that which may be known of God is manifest in them; for God hath shewed it unto them. For the invisible things of him from the creation of the world are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even his eternal power and Godhead; so that they are without excuse.” Romans 1:19, 20

God loves you (& all mankind)

We believe that God is not a Creator who made us, lost interest, and moved on to other things ages ago. “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” John 3:16 God, for whatever reason, cares about us, not only as part of a collective like ‘the children of Israel’ or ‘the Church’ but loves each of us as individuals.

What this means for fiction

Christians, real or fictional, don’t have to be embarrassed about our belief in God when faced with the local atheist. Atheists are not better than us, smarter than us, or cooler than us. We should look on an atheist the way we look on a guy who hasn’t learned his multiplication table all the way through yet— as someone who does not yet know vital facts about the world.

Christian fiction writers should not perpetuate the old myth of the logical atheist/secularist and the emotional/illogical ‘person of faith.’ This trope needs to die, disappearing like a soap bubble in the light of the truth like a vampire in sunlight.

Part 2 is coming soon — in two weeks, on April 9th. But if we have enough response with people sharing, Tweeting and otherwise spreading the word about this post, I may get on the ball and get it posted in one week. Comments this post are, as always, welcome.

Wattpad: I am syndicating my poetry book, Where the Opium Cactus Grows, on Wattpad. My profile there is: https://www.wattpad.com/user/NissaAnnakindt

One of the books I’m reading on Wattpad is Unicorn Western by Sean Pratt and Johnny B. Truant. It’s kind of like Stephen King’s Dark Tower. And like High Noon. Not Christian fiction, but so far it is a fun story.

Left Behind: Thinking Characters and Flashbacks in 1st Chapter

Recently I was re-reading one of my how-to-write books by Christian author James Scott Bell, and he spoke of how many first time writers write a novel beginning with a character just sitting, thinking. Often the thinking includes thinking about loads of backstory items, which make that opening into an info-dump.

Recently I was re-reading one of my how-to-write books by Christian author James Scott Bell, and he spoke of how many first time writers write a novel beginning with a character just sitting, thinking. Often the thinking includes thinking about loads of backstory items, which make that opening into an info-dump.

And then I went upstairs to get something to read and I picked Left Behind, a bestselling Christian novel which made the whole nation aware of the Rapture theory, which was previously pretty obscure even among Christians. And I noted that the first chapter began with main character Rayford Steele, a pilot, sitting in the cockpit thinking.

Now, we know that Jerry B. Jenkins, writer of the series (LaHaye was the theologian and prophecy-wrangler) was not a bad writer. In the author bio in the back of the book it tells that Jenkins had written over 100 books at that time. And Left Behind went on to be a major bestselling book which crossed over into secular audiences. So we know that sitting-and-thinking opening worked. But why did it work?

The scene in question begins on page 1 of my paperback copy and goes on to page 5. I think that the main reason it works was that what Rayford was thinking about was, in fact, adultery.

Now, most people who don’t normally read Evangelical Christian fiction think that is all about devout and perfect Christians who never swear, drink or pick up a deck of cards. So when Rayford starts off thinking about adultery, and about how he feels okay about that because he is ‘repelled’ by his wife Irene’s ‘religious obsession.’

Non-Christian readers (I was non-Christian when I first read the book) were reassured that Rayford was a ‘guy like us’ who wasn’t a religious fanatic or holier-than-thou. Devoutly Christian readers, on the other hand, got the idea that Rayford was not actually a believing Christian but a nominal Christian who went to church only for social purposes and thought that ought to be good enough for God.

The sitting-and-thinking opening also introduce us to some basic facts— the makeup of Rayford’s family, the fact he had not ever cheated on his wife but he was thinking of changing that, and the fact that he was currently flying a 747 airliner over the Atlantic to Heathrow.

Another important bit of info Jenkins is slipping us is the fact that Rayford’s wife had become interested in Bible prophecy and that she believed in the Rapture theory and had told her husband enough that he knew about it (and was not interested.) This is essential setup for the rest of the chapter when Rayford discovers that a number of passengers had disappeared from the airplane and had left their neatly folded clothes behind.

The first chapter goes from Rayford’s thinking-about-adultery scene to another scene that does something that writing teachers warn against in first chapters: it goes into a flashback. The flashback involves a second major character, Cameron Williams, who is a reporter and flashes back to an exciting event he had witnessed in his reporting career— a seemingly miraculous event which thwarted a Russian attack against Israel. (This event has Bible-prophecy significance to the story.)

The problem with a first-chapter flashback, as a writing teacher will tell you, is that you are jumping away from the present story to follow a barely-known character into the past. This break, when poorly done, can make a reader put down a book, never to resume. I mean, it’s harder to stay interested in the story when the author is making you jump around in time before you have even gotten interested in the characters! I have sometimes gotten quite lost in a story because I have a habit of skim-reading especially when part of a chapter seems boring. I can miss the clues that a flashback is starting and wonder what the heck is going on.

The flashback works in this case because it is action-packed, and shows Cameron Williams in action as a reporter willing to go to dangerous places to get a story. It might not have been the best choice for the chapter, but it did get one of the authors desired Bible-prophecy events checked off the list. And it establishes the key fact that Cameron Williams believed in God but had not become a Christian by this point— something essential to establish since the Rapture was going to hit before the end of the chapter.

As a reader, I found that first chapter quite exciting enough to get my attention. I was not a Christian at that time, but when I had been Christian, I had never been in a church that taught the Rapture theory. When I read it I kind of took a superior attitude and thought I knew better than those dumb Evangelical Christians. But I enjoyed the book, and the series, as exciting futuristic disaster-fiction. Probably a reader today might call it ‘dystopian.’

Note: if you are unfamiliar with the Rapture theory, Protestant historian Dave MacPherson has traced the origin of the theory to a private revelation to a young Scottish lady in the year 1830. This private revelation, when made known, impressed some preachers in a church called the Plymouth Brethren who were interested in Bible prophecy. One of them was C. I. Scofield who produced the Scofield Reference Bible which is a popular book to this day. MacPherson has written a book on the history of the Rapture theory as he has discovered it in Plymouth Brethren writings of the time, The Rapture Plot. If you belong to a church or denomination which does NOT teach the Rapture theory, I think it might be a good idea to read MacPherson’s book if you are planning to read or re-read the Left Behind series so you will understand that the Rapture is not a universal belief of all Bible-believing Christians.

Broad-spectrum Christian fiction

For some people, Christian fiction means Evangelical Christian fiction— books from a handful of publishers representing an handful of flavors of Evangelical. “You can’t write Christian fiction, you’re Catholic!” is what you hear from the naysayers.

For some people, Christian fiction means Evangelical Christian fiction— books from a handful of publishers representing an handful of flavors of Evangelical. “You can’t write Christian fiction, you’re Catholic!” is what you hear from the naysayers.

But Evangelical Christian fiction is not the sum total of Christian fiction. It arose, I think, because there were once a large number of Evangelical churches who condemned reading ‘worldly novels’ the way they condemned drinking alcohol, dancing and wearing make-up.

The problem is, Christians are readers. Protestant/Evangelical Christians are urged to have daily Bible reading habits. Catholics are often urged to do Lectio Divina — aka Bible reading— and to read Catholic religious books. So it’s natural that those Evangelicals who were taught that reading ‘worldly novels’ was wrong wanted some non-worldly fiction to read. You can’t read prayer books and sermons forever.

Evangelical Christian fiction has done well for itself. The ‘Left Behind’ series showed that even Evangelical fiction with strange theology most Christians didn’t know about (the Rapture theory) could become best-sellers, going far beyond the realm of Evangelical Rapture-believers. (Some Evangelicals don’t believe the Rapture theory.) I was a Norse Neopagan when I got hooked on the Left Behind books.

At one time most of the fiction produced in Western Civilization was written by Christians. Some of them, like Machiavelli, author of ‘The Prince’ may have been only nominal Christians— Christians in name only. Christian themes in fiction were normal and acceptable. Think of Jane Eyre, or Dracula. There was enough Christianity there that if they were first written today, most literary agents and publishers would demand the books be secularized to be published.

When I was in school at San Jose Christian School, our teacher Mrs. Stark had a group of novels at the back of the room that were very Protestant Christian fiction. One was set in Germany at the time of the Protestant Rebellion (“Reformation”) and the characters were all associated in some way with Martin Luther (founder of the Lutheran church.)

I have also read old Catholic novels from the 1950s, and I have read the books of Orson Scott Card, a man of the Latter-Day Saints church who managed to become a Hugo Award winning writer without hiding his faith. His ‘Lost Boys’ is a story featuring an LDS family who are living out their faith.

I think that Christian fiction readers and writers need to take a broader view of Christian fiction. Is it really better for an Evangelical Christian to read a secular book by an angry atheist than to read a Catholic author? We are all followers of Jesus Christ even if some of us have *wrong* theology.

Some people would say it’s OK to read Catholic, Protestant and Evangelical fiction, but they draw the line at Mormon. After all, that religion is in the book ‘Kingdom of the Cults.’ Well, is that how we are called to judge other Christ-followers— by whether their church is in the book ‘Kingdom of the Cults?’ As a Catholic I believe that the Mormon teachings include a lot of incorrect theology. But isn’t Mormon fiction a little closer to what we should be reading than fiction that calls Christians ‘haters’ and ‘unintelligent’, and promotes angry atheism?

Christians/Christ-followers of different kinds can work together to make Christian fiction a more viable and exciting genre. We can help authors sell their books and readers find new reading material. It’s better to work together that to break up into ever-smaller groups looking for only writers with perfect doctrines.

The image above is of Catholic author Karina Fabian’s sci-fi novel Discovery. I read it cover to cover and when I had come to the end, I liked it enough to immediately start again at the beginning and read it a second time. I very much recommend it to sci-fi fans.

Why Christian/Catholic Authors shouldn’t write smutty books

Everybody does it, these days. Sex scenes in fiction are oddly considered ‘realistic’ and some unfortunate readers refuse to read books without them. But a Christian (includes Catholic) author must not do it.

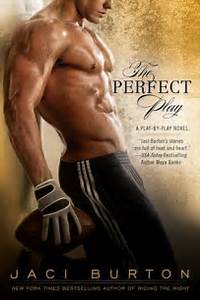

Note: the book cover above was chosen at random. I don’t know the author or if the book is as ‘sexy’ as the cover indicates.

Why not? Plotting a sex scene involves cultivating a sexual thought, on purpose. In Christianity that is called ‘entertaining impure thoughts.’ HAVING impure thoughts is not the sin– we have no control when we wake up from a sex dream and continue having sexual thoughts before our self-control can assert itself.

There is an old Catholic story about a teen boy who goes to confession and can’t think of what to confess. The helpful priest asks if the boy has been entertaining impure thoughts. The boy, wanting to be truthful, says ‘No, Father, they entertain ME.’

Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, and many other fine authors that we all should read managed to write novels without having their characters go at it sexually all over the landscape. Dickens even wrote prostitute characters without resorting to sex scenes. Why today’s authors think they are better and more realistic than Dickens because they write their sex fantasies into their fiction I do not know.

A Christian is called to be pure. Why? Because sex is too holy to be taken casually. God instituted marriage so that believers could live out their sex lives in a pure and holy way. Marriage— and the sexuality that comes with the marriage— is symbolic of the relationship of Christ and the Church. What part of that makes you believe that writing out sex fantasies in our fiction is OK?

Some people think that you need explicit sex scenes to be ‘realistic’. It would also be ‘realistic’ to have an explicit scene of your character’s next bathroom visit. But it would also be crude and disgusting to many readers. Do we really need to know if Harry Potter did a number 1 or a number 2?

Another reason against sex scenes is the unintended effect we may have. We write a gritty, realistic rape scene that is as unsexy as we can make it— and some teen uses it for whacking-off material. Won’t that warp the young person’s sexuality? And what about the recovering sex addict? A sex scene, unexpected in a Christian author’s novel, may cause a relapse.

A very pragmatic reason against sex scenes for the Christian/Catholic author is that the reader base for Christian fiction overwhelmingly prefers traditional fiction without sex scenes. What do you do when the Christian readers reject you? Secularist readers won’t like you unless you reject all your Christian values in a way you probably don’t want to do.

Finally, writing a sex scene can be overly revealing about you-the-writer. It’s hard to write a sex scene without drawing on your own personal sex experiences, if any. And even if you are innocent of experience, folks will figure that you are doing that kinky sex thing you wrote about.

I should at this point admit that when I first started out writing I tried to write a porno. I had to buy some porno books to get the sex scenes right. I wrote one chapter with a lesbian scene and then lost interest in the project. I realize now what a mistake it would have been to have continued with that project.

Finally, brethren, whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report; if there be any virtue, if there be any praise, think on these things. Philippians 4:8 KJV

New opportunities in Christian fiction

Christian fiction— perhaps it will go down in history as the genre most harshly judged by critics who don’t read the genre. But Christian fiction has a place, and that place is widening.

Christian fiction— perhaps it will go down in history as the genre most harshly judged by critics who don’t read the genre. But Christian fiction has a place, and that place is widening.

My earliest memories of Christian fiction were of fiction sold only in specialty Evangelical Christian shops. My impression was that it was mainly designed for members of strict Evangelical groups who taught that Christians don’t read worldly novels— or drink, dance or own a deck of playing cards.

Our family wasn’t that kind of Christian. We were Presbyterians, and went to PCUSA churches— though the church had not fallen away from Christian teaching so badly at that time. We read ‘normal’ fiction. Though my mom had a novel called ‘The Silver Chalice’ which was VERY Christian in tone and told the story of the Early Church. But that novel was brought out by a mainstream publisher, and later was adapted into a Hollywood movie.

My, how the times have changed! Modern publishers don’t care to retain their Christian readerships. Mainstream novels are full of references to Christians of all sorts as ‘haters’— because the authors think it’s ‘hateful’ to oppose aborting children or oppose calling gay relationships marriage. Publishers not only don’t object to it, they seem to almost require it. And although Christian readers have adapted to this bigoted atmosphere enough to be able to read anti-Christian-biased fiction, it’s often hard to enjoy it. Particularly when authors accuse Christians of all being ignorant, while displaying their own ignorance of the commonest details of the faith they are hating.

Evangelical Christian fiction got noticed when the ‘Left Behind’ series started to hit the best-seller lists. It was helped along by the fact that secular folks got really interested Christian beliefs about the End Times about then, since they believed that the Evangelical End of the World would happen in the year 2000. This was a false belief— the REAL Evangelical End of the World happened in 1988 (40 years— one Biblical generation— after the founding of the State of Israel.) But it sold a lot of exciting books filled with Christian characters to people who might have been in spiritual need of them.

But now in the Internet age, the picture has changed. For one thing, Christian authors are connecting across church/denominational lines. In my Christian Science Fiction & Fantasy FB group we’ve had Evangelicals of many sorts, Protestants, an Episcopalian monk, Catholics, and a Mormon or two. And so we are more aware that sound Christian fiction can come in many ‘flavors’— though we disagree on the authenticity and usefulness of some of the ‘flavors.’

The indie fiction revolution means that Christian fiction writers are no longer out of luck if their denominational background is not accepted by the bigger Evangelical fiction publishers and their own church’s publishing house doesn’t accept fiction. Along with Evangelical fiction, Catholic fiction and LDS (Mormon) fiction, all of which have traditional publishers, the most obscure denominations, like WELS Lutherans, can have fiction tailored to their church background.

Because of indie fiction, individual Christian authors no longer need be restrained by old-fashioned and silly-seeming Christian fiction rules. For example, some of the old Evangelicals wouldn’t allow Christian characters to be shown drinking alcohol, dancing, or playing innocent card games, because some readers would have objected.

The indie freedom has its downside, though. Many Christian writers have read far more secular fiction than Christian. They also often have had very little if any religious education. I know of a number of young Christian girls who see nothing wrong with sex outside of marriage and cohabiting relationships, so long as the partners claim to be engaged. It’s perfectly possible that there are some young indie authoresses out there writing ‘sexy’ romances in which the characters are Christians, and who market their work as Christian romance. It won’t sell to the Christian market, and secular romance fans probably won’t touch it because of the Christian label.

Indie Christian fiction, then, is less ‘safe’ than traditionally published Christian fiction which has been vetted to death for offensive things, even trivial ones. But, as in secular indie fiction, that adds to the excitement of reading and discovering new indie authors. It helps to follow Christian fiction blogs and web sites which review indie and small press books as well as those from the big Christian publishers. They can help you find books which you might enjoy and warn you about any content concerns such as excesses of ‘magick’ in a fantasy novel.

If you are a writer and a Christian, it might be well to consider whether the wider world of today’s Christian fiction might be the right place for your writing. Pitching your book to fellow Christians might be a wiser move than aiming at secularists who might reject your work if they learn about your faith.

Will I review your great new Christian indie novel? Probably not. I am a very slow book reviewer and I have a backlog of books written by friends I must review. Also, I don’t enjoy every possible subgenre within Christian fiction. If you have a great contemporary romance, it probably won’t catch my interest enough to finish it even if you are the best romance writer ever! But, don’t despair. I am hoping to recruit a couple of Christian authors who will do a little guest posting of reviews for this blog. (How do you get your Christian book reviewed in the meantime? Join appropriate Christian author groups, make a few friends there, review THEIR books, and perhaps you will be able to arrange to trade reviews.)

One blog for (Evangelical) Christian fiction writers is Mike Duran’s deCompose. Here is a sample post: The Importance of Implicit (vs. Explicit) Christian Content in Fiction

My FB group for Christian writers of science fiction and/or fantasy:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/366357776755069/

Now, this group, being on FB, does not actually BAR non-Christians from joining. However, since the topic is the problems of CHRISTIAN writers in these genres, non-Christians rarely have much interest in the group. But all are welcome to join.